Humans are adaptable creatures, modifying their living environments to meet their needs. Historically, residential buildings were characterized by continuous changes driven by the evolving needs of their occupants (Konieczna, 2018). Architecture, too, has evolved and developed to serve the changing needs of societies. The social environment is constantly shifting, and architecture must adapt accordingly. These adaptations occur over generations, with improvements based on feedback and the survival of the fittest according to specific criteria (Verma, 2022).

The Living Façades

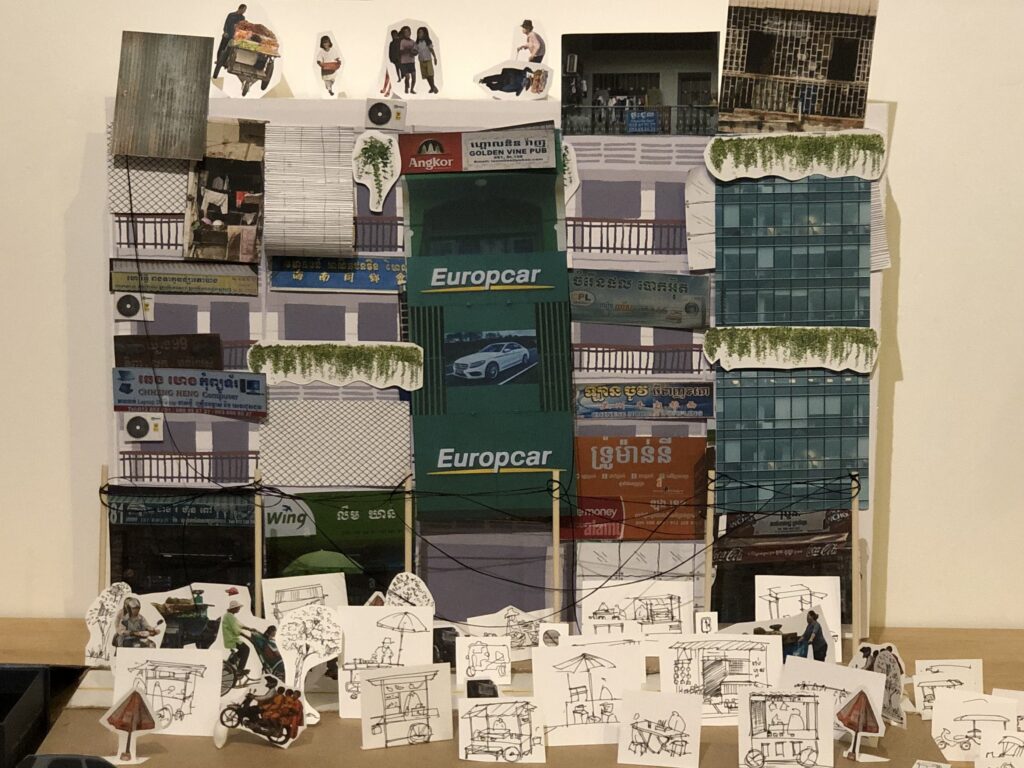

“The Living Façades” explores the evolving nature of typical Phnom Penh houses, portraying them as dynamic entities that both reflect and shape the city’s cultural identity. By examining the building surfaces, this project uncovers the hidden stories of how facades have responded to social, economic, cultural shifts and regime changes, revealing multiple layers of urban activity. This exploration demonstrates how people continually adapt their living spaces to accommodate their needs, offering deeper insights into Phnom Penh’s evolving identity. Moreover, The Living Façade serves as a modern archive, encapsulating the evolution of the city’s shophouses.

The interactive building façade model serves as a canvas for audiences to explore the various add-ons found on real building facades in Phnom Penh. It acts as an amalgamation of the city’s built forms, allowing participants to connect the model to their own experiences, whether through witnessing the city’s transformation or making adaptations in their own homes. The model is inspired by real-life scenarios, incorporating elements such as human activities, patterns, and other existing features that reflect the daily lives of Phnom Penh’s residents.

Phnom Penh’s typical housing forms have undergone significant changes over time, reflecting ideological shifts, resilience during crises, economic booms, and the complex needs of its inhabitants.

Contemporary Phnom Penh can trace its architectural evolution back to the colonial era of the 1860s and continuing to the present day. Seven pivotal periods in Cambodia’s history have profoundly shaped the capital city’s built forms.

French Colonial (1860s – 1953)

One of the most prominent and abundant architectural styles in Phnom Penh during the colonial period was the Chinese shophouse. This design, a blend of Chinese and colonial architecture, was typically owned by Chinese merchants and played a crucial economic role in the city as the center of commercial trade.

Songkum Reastr Niyum (1953 – 1970)

The Sangkum Reastr Niyum era, led by Prince Norodom Sihanouk, saw a significant transformation in architecture and urban planning. The prince used these elements to symbolize the new regime, drawing inspiration from Western socialism. This period marked the rise of New Khmer Architecture, visible in many public buildings across Phnom Penh. The Cambodianized Chinese shophouse — narrow, multi-story buildings with ground-floor commercial spaces — became the standard urban building form.

Khmer Republic (1970 – 1975)

During this period, Phnom Penh’s population more than doubled, from around 630,000 in 1969 to approximately two million by 1975. The influx of rural refugees fleeing both the advancing Khmer Rouge and U.S. bombing campaigns turned the city into a massive refugee site. To accommodate the growing population, informal and makeshift settlements were constructed.

Khmer Rouge – Democratic Kampuchea (1975 – 1979)

No urban development occurred during the Democratic Kampuchea period. The city’s urban life was abruptly disrupted, with two million residents and refugees being forcibly evicted to the countryside. Although the Khmer Rouge did not engage in large-scale destruction of buildings, they caused significant damage through negligence, failing to maintain the entire city’s infrastructure. Estimates suggest that between 5,000 and 20,000 people remained to keep basic infrastructure functioning and work at some manufacturing sites.

People’s Republic of Kampuchea (PRK, 1979 – 1991)

Under communist Vietnam’s protection, urban development in Phnom Penh slowly restarted. Informal urbanization characterized this period, with spontaneous settlements filling much of the city. Concrete structures and add-ons became the dominant building material during this time.

United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia - UNTAC (1992 – 1993)

During the UNTAC period, the communist economic system was dismantled in favor of a free-market economy, signaling the beginning of economic growth. Damaged housing from the Khmer Rouge era was repaired, and the city’s built forms began to resemble Western architecture due to the influx of foreign influence and capital.

The Kingdom of Cambodia (1993 to Now)

In 1993, the monarchy was restored, with King Norodom Sihanouk returning to the throne. Phnom Penh entered a period of rapid urbanization and economic development. The construction boom began in the mid-2000s, leading to the development of high-rise buildings and skyscrapers. Today, the city includes several satellite cities, developed by large investment conglomerates.

This project is part of a week-long workshop organized by the Center for Khmer Studies titled “Repurposing Phnom Penh: Built Forms and Infrastructure as Archive.” The Living Façades was created by a four-member team.

Myself

Master Student, Beijing Forestry University

Graduate, Royal University of Fine Arts

Senior, Royal University of Fine Arts

For more information about the workshop, head over to Center for Khmer Studies event site.

References

Konieczna, D. (2018). Modern trends in the formation of adaptive architecture. Technical Transactions, 9. https://doi.org/10.4467/2353737xct.18.128.8967

Verma, S. (2022, October 22). Responsive to Adaptive – The shifting trends in Architecture – Arch2O.com. Arch2O.com. https://www.arch2o.com/responsive-to-adaptive-the-shifting-trends-in-architecture/

Ng, K. (2020). Book review: Urban Asias: Essays on Futurity Past and Present. Urban Studies, 58(2), 455–457. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098020961016

Kolnberger, T. (2020). Continuity and change: Transformations in the urban history of Phnom Penh, Cambodia. In transcript Verlag eBooks (pp. 219–238). https://doi.org/10.1515/9783839451717-014